The HA Secondary Committee have been working hard to ensure that young people have an opportunity to engage with the work of the HA, not only through being able to access resources and take part in opportunities but to have their voices heard. We have run the Young Voices project where students from across the country took part in online discussions and mini research tasks to present what young people thought about school history and recently they had the opportunity to take part in a survey to help inform the HA response to the Curriculum Review. Now we are offering students the opportunity to have their work published on OBHD as an opportunity to share their work to a much wider audience. We hope that you enjoy reading Rafferty’s essay as much as we did.

Slavery: A case study comparison between the Achaemenid Empire and pre-Hellenistic Greece

By Rafferty – a Year 9 pupil at The Crypt School, Gloucester.

Slavery, despite being unique to each respective nation based on their economic, social and political characteristics, was a common and generally acceptable practice in both Ancient Greece and the Achaemenid Empire – in this context, referring to the years between the approximately 6th Century BCE to the 4th Century BCE, or in a Greek context, the pre-Hellenistic Era. But – what exactly were the differences between each civilisation’s own slavery systems? How were slaves treated, where were they from, and how commonplace was their usage?

Bandaka, Kurtaš, and Māniya

In the Achaemenid Empire, slavery was a common occurrence, although historians remain divided on whether it was actually a major pillar of society and economic development for the region. King of Kings Darius the Great (who reigned from 522 BCE to 486 BCE until his death) described his military colleagues and generals as ‘bandaka’, the Persian translation for ‘servant’ or ‘vassal’, alluding to a larger hierarchy in the Achaemenid Empire ranging from the King of Kings (in this case, Darius I), followed by his generals, soldiers, and finally, the common people.

It should be noted, however, that ‘bandaka’ does not refer to actual enslaved persons, but instead to servants, in this case meaning the military comrades who were considered by concurrent historians to all be considered ‘servants’ to the King, as were the people. Slaves, on the other hand, were not construed in quite the same sense. Other Persian words such as ‘kurtaš’ and ‘māniya’ were used to indicate indentured – and sometimes enslaved – workers, who are seen by both modern and ancient historians to be a separate class to ‘bandaka’.

How were slaves seen in the Achaemenid Empire?

It is an important historical fact that slavery was previously recorded across Babylonia, Media and Egypt, and therefore the practice of enslaving and exploiting people was already widespread and likely not treated as a taboo or unethical act.

As opposed to the private ownership of slaves popularised and practiced a few millennia later by the Transatlantic Slave Trade, which focused on chattel-based enslavement, with enslaved persons usually being owned and used by wealthy individuals, rather than the state itself, the majority of enslaved persons in the Achaemenid Empire were government/state owned, although private ownership did exist to some extent.

Many slaves were seen as property of the Persian state, and often utilised as agricultural labourers tied to the land that they worked on. Despite this, slavery is considered by contemporary historians and scholars to have been treated with a low level of importance in the Achaemenid Empire. For example, the capital of Persia, Persepolis, was constructed using almost entirely paid labour, which is generally considered to have been sourced and treated with reasonably ethical standards (bear in mind labour standards in the 400s~ BCE were far different to how they are today).

In terms of how slaves were actually treated and where they were primarily sourced from, slaves were gathered and owned all across the ancient world, including in Babylonia – an agreement with the Babylonians was reached which forced them to provide a tribute of 500 boys to Achaemenid aristocrats. Defeated Eretrians and Ionians were also often forced into slavery upon being captured during conflict, in a similar fashion to how various Greek states sourced their enslaved population. These enslaved civilians were seen as symbolic prizes and trophies following the defeat of their country of origin.

An incorrect translation of the cuneiform text inscribed into fragments of Cyrus the Great’s cylinder has been popularised across the internet, attesting that he abolished slavery, among other things including the false notion that he ‘believed in self determination’. However, this claim has been disproved.

Slavery in Classical Greece

Due to the length of recorded Greek civilisation – which, according to modern estimates dates back to 2200 BCE, when the Minoans first began to inhabit and successfully settle in the Mediterranean island of Crete – information on enslavement is difficult to accurately date and measure, meaning that it is necessary to establish our knowledge on the topic of Classical Greek slavery based upon a mixture of contemporary and historical sources.

However, what historians do know is that chattel slavery was widespread and widely accepted throughout various Greek states such as Athens, Corinth and Aegina. During the 5th century BCE, the number of enslaved persons was estimated at 80,000 slaves, who were often captured and forced into slavery following their imprisonment during conflict, or traded from the surrounding ancient world, including civilisations such as Lydia, Macedonia and Syria. The population of Thebes was reduced to enslavement following Alexander the Great’s (b. 356 BCE, d. 323 BCE) takeover of the area, who was also responsible for the development of an enslaved populace consisting of defeated Olynthus citizens. Similarly to the Achaemenid Empire’s tactics, the capture of defeated enemies was symbolic to the strength and power of the Greek Empire in both the Hellenistic and Classical ages. Around 300 Scythian archers were supposedly employed as an Athenian police force. In these ways, slavery was indeed racially and ethnically motivated and based.

Contemporary scholars and historians offer varying interpretations of how widespread slavery itself was – some sources such as the famous orator, Hypereides, claim that most civilians living in the Greek states owned at least one slave, which while debated in other sources, does perhaps hold some truth considering that the practice of slavery was so widespread across Athens, Corinth and Aegina (as well as other states).

How were slaves treated in Ancient Greece?

Slaves were treated with varying degrees of abuse depending on their social status and hierarchical class, and Aristotle sums up their experience with the phrase ‘work, discipline and feeding’, implying that their working conditions were rather austere, lacking much comfort or luxury and focusing instead upon basic needs, namely including food and a strict disciplinarian lifestyle; to this day, imagery of slaves being flogged and bound by their masters exist in various artistic forms. An informal ‘hierarchy’ of sorts was installed into many elements of Greek society, for example, skilled craftsmen were treated with a much higher level of both care and societal respect than their farming counterparts, who could be subjected to harsh punishment should they fail to meet their masters’ demands.

Ancient Greek education and schooling, particularly formal learning – specifying the attendance of a public school or classes with a hired tutor – was typically reserved only for males and non-slaves, meaning that many slaves were illiterate and uneducated.

Though Athenian slaves belonged to their masters and were generally seen as property, there are existing records detailing the few rights bestowed upon them. Interestingly, despite their harsh treatment by many commercial hirers, Athenian households often regarded enslaved cleaners and workers to be a part of the family, and some instances of them owning their own private property are documented, as well as significant evidence indicating that they were allowed to practice religion freely in the household of their owner, who was prohibited from physically abusing them. Upon arrival at their new owner’s residence, they could be welcomed with gifts, and whilst Athens is sometimes incorrectly considered the only slave trading hub of the Greek city states, sizeable chattel slavery markets existed around other parts of the ancient world, such as Attica and Ethiopia.

Comparison

Despite evidence that slavery existed in both the Achaemenid Empire and their contemporary Ancient Greek counterparts, evidence on the societal significance and organisation of the slave trade shows major differences between the two civilisations, not to mention the differences in treatment of individual enslaved persons.

To begin with, the ownership of the enslaved population differed greatly; in Persia, slaves were generally owned by the Persian state, who controlled how they were used and treated, often putting them to work in agricultural fields, tending to state owned land. Despite some private ownership likely also existing alongside the state owned enslaved population, the slaves themselves were not as widely used for the construction of the Achaemenid Empire as they were in Greece. Case in point, the great city of Persepolis is believed to have been constructed with minimal usage of slave labour – or possibly none at all. This, combined, shows a reasonably coherent argument that enslaved people did not belong to private owners, and were generally owned by the state. In Greek city states such as Athens and Corinth, where slavery was most prevalent, this standard of government owned slavery did not exist to such an extent, and many enslaved persons belonged to private owners, focusing on the mantra of ‘work, discipline and feeding’, highlighting a comfort-lacking existence which could be accompanied by exploitative treatment and abuse – however physical abuse was prohibited in slave-owning households.

The sources of enslaved people were rather similar in the respects that they were gathered from all across the Ancient World, particularly the Near East – both the Achaemenids and the Greeks were believed to have captured defeated civilians and soldiers from conquered states, who would then be forced into slavery or other means of labour. The status of these captured slaves existed in both societies, as they were viewed as prizes of victorious battle, which is a societal construct encouraged and promoted in both Greece and Persia.

Conclusion

In conclusion, whilst both Greece and the Achaemenid Empire practiced slavery actively during the 5th and 4th century BCE, the city states of the former practiced enslavement in a much stricter and more systematic manner, with slavery’s presence being noticeable in all aspects of daily life in Greek society. Slaves were not just owned by the rich elites, but were parts of households, and had only the most basic needs fulfilled by their masters, cited by Aristotle as focusing on ‘work, discipline and feeding’, and thereby seeming to focus primarily on efficiency as opposed to the wellbeing of individual in slaves persons.

In Persia, despite the ruling elites owning some slaves of their own – a practice reflected in Greece – most enslaved people were owned by the government and often put to agricultural work. Whilst slavery could be – at times – strict and brutal in Athens, as well as various other Greek states, existing records on the Achaemenid Empire indicate that slaves were treated with considerable dignity and ethical standards are believed to have been in place. The hierarchy was also different – with a focus on societal classes such as bandaka and kurtaš which defined how Persian society was formed. Whilst actual indentured servants and enslaved persons were treated with reasonable standards, everybody was considered a slave to the reigning monarch, whether it be a soldier or a normal middle class civilian. Whereas in Greece, citizens of the city states are believed to have lived in a more democracy and ‘free’ society.

Of course, it is to be noted that these civilisations existed millennia in the past, and as such labour rights and ethical standards have changed dramatically since, especially as we today still grapple with the long and painful legacy of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, which has forever changed historians’ views when it comes to human rights and dignity. When we reflect on the Persian capture of Babylon youth, or perhaps the Greek ban on education for enslaved people, we can only hope that, looking forwards, we can better understand the struggle of enslaved people over time, and through this newfound lens, appreciate the standard of freedom that so many enjoy today. But, we are still a long way away from securing justice for everybody. Perhaps with the lessons we’ve learnt from the Achaemenid Empire and pre-Hellenistic Greece combined – we can get just a little closer to that goal.

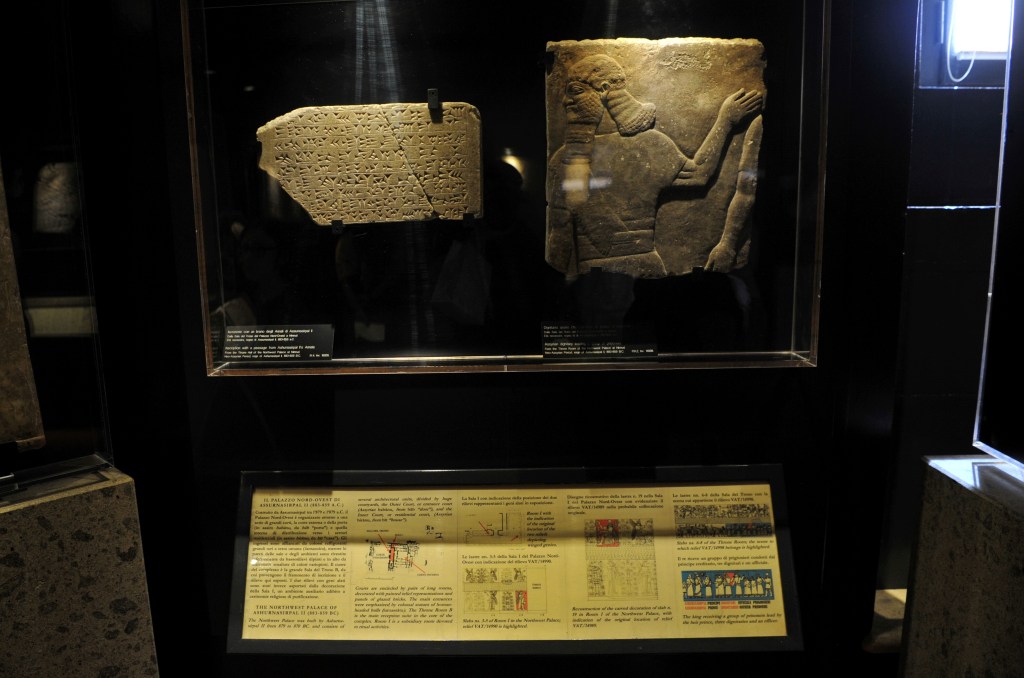

Pictures: Achaemenid stelae at the Vatican Museum