Pete Jackson from Ryedale School in North Yorkshire and Ben Bassett from Villiers School in London have been working on writing historical stories to support the GCSE Curriculum. Here is their findings and examples of their work

The thinking behind the project

Inspired by the growing momentum around historical storytelling in the classroom, we’ve spent the past year crafting narrative-rich resources to support the OCR B GCSE History curriculum. Our aim? To harness the cognitive power of stories to deepen students’ understanding and make disciplinary thinking vivid and memorable. Through our collaboration, we have refined our work and hope to share some of the pedagogical principles behind writing historical stories. We believed that retrieval practice alone could not secure historical learning unless students first encoded knowledge in meaningful ways. Reflecting on Daniel Willingham’s ideas in his book Why Don’t Children Like School? Stories offered a vehicle for that encoding, holding attention while also embedding concepts. Christine Counsell’s argument that they can do the ‘heavy lifting’ of curriculum knowledge gave us the confidence to pursue this approach.

What are our three guiding principles?

We set out from the outset to make sure that these historical stories would not be a quick fix for curriculum planning. Our stories would be crafted and thoroughly researched – this was a labour of love rather than a quick fix to jump on the storytelling bandwagon. Within our work we came up with three guiding principles.

- Root stories in scholarship

Our stories had to be rooted in scholarship, drawing on sources and historians rather than slipping into fiction. As Rich Kennett put it in his keynote lecture at the fantastic Ark Soane conference in 2025 – stories should have: “People, Place and a Pinch of Discipline.”

- Be clear about curricular purpose

We wanted every story to serve a clear curricular purpose. Students did not need to recall every detail but encounter the core knowledge or conceptual understanding that the story was designed to covey.

- Craft the storytelling carefully

We paid close attention to how the stories were told, recognising that tone, pace and pauses mattered as much as content in creating lasting impressions.

Stories we have worked upon

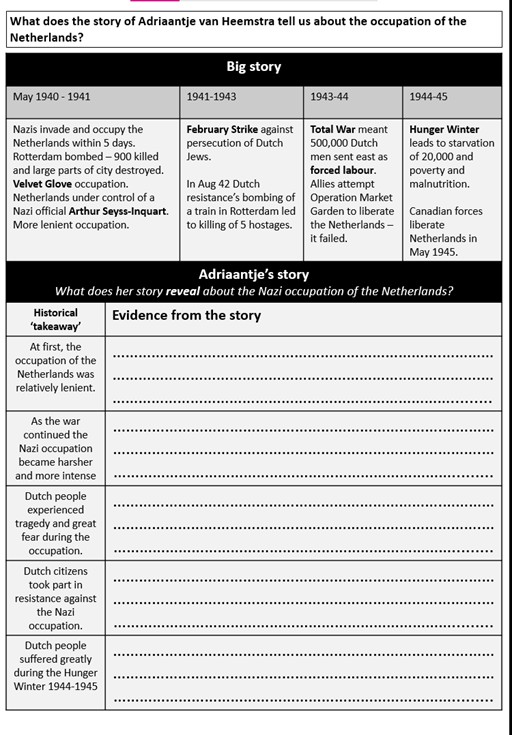

Throughout the year we have worked on almost twenty historical stories together. Highlights include using the story of Audrey Hepburn to teach about the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands and using the story of Thomas Platter to teach about the Elizabethan theatre.

In the process of writing our HA conference session on using powerful storytelling at GCSE, we came up with ten top tips for using stories well in the classroom. These are inspired by collaboration with others as well as our reflections on our working together.

1. Work with and learn from others

The essence of One Big History Department and the fantastic community of history teachers is that we all work together. Most of the time, we have simply been ‘standing on the shoulders of giants’ and been inspired by great thinkers in the history community.

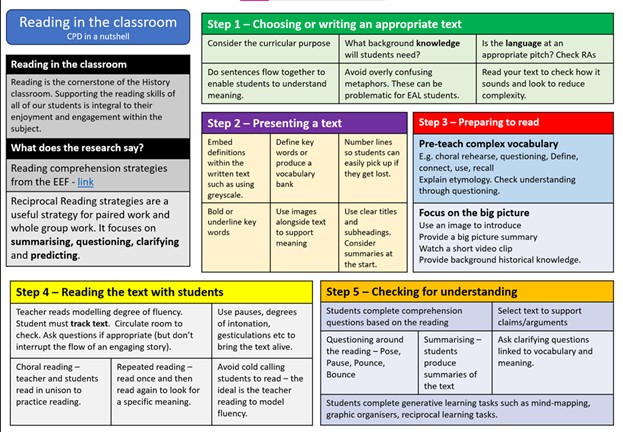

2. How do you support reading in the classroom

To make storytelling effective, we needed to be deliberate about how we teach reading in the history classroom. To support this, we created a CPD sheet offering practical strategies for integrating reading into lessons.

3. Line numbers

Adding line numbers fundamentally transformed how effectively we could use stories in the classroom. They make it easier for both teachers and students to track where they are in the text, improving accessibility and supporting focused discussion. They also enhance consolidation tasks, allowing us to direct students to specific parts of the story and highlight the key knowledge we want them to take away.

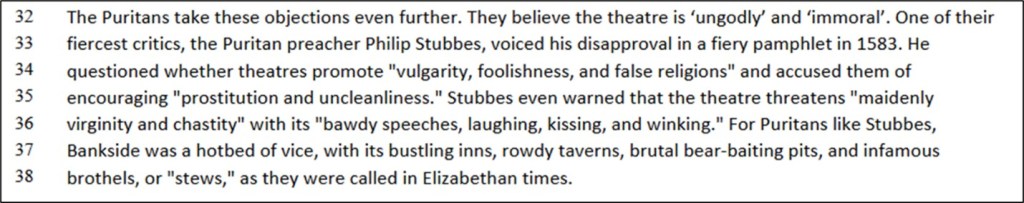

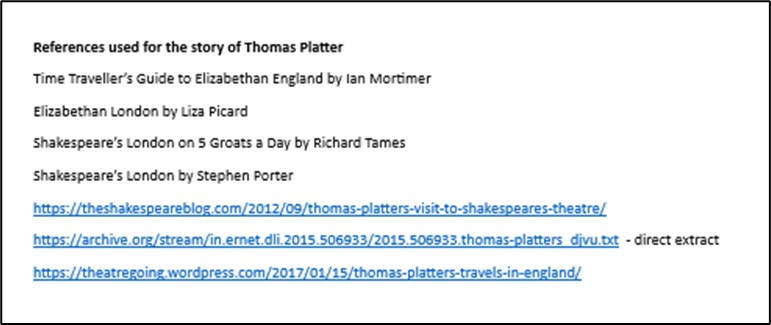

4. Put sources at the heart of the story

Too often, historical sources are treated as detached ‘gobbet-style’ exercises which don’t let students see how evidence and interpretation interact with each other. Worse still, they are reduced to formulaic nature-origin-purpose tasks. In our project, we wanted to put the sources at the heart of our story. We found when directly woven into the narrative, it made the story feel more authentic. In addition, we think that it is important for the teacher to include references at the end of their stories, and to point out where the evidence comes from so students can see how evidence supports interpretation and brings an authentic disciplinary dimension to their learning.

One example is our use of Thomas Platter’s diary to explore Elizabethan theatre. Rather than analysing short extracts in isolation, we built the story around his experience of attending a play in London. His vivid descriptions were used to frame the sensory world of the theatre — from the smells and sounds to the energy of the crowd, and the intriguing story of the fireworks attached the monkey. When teachers point out these embedded sources during the story, it helps students connect knowledge, evidence, and narrative in a meaningful way.

5. Stories make the abstract concrete

The story of Bess of Hardwick teaches students about the rich in Elizabethan times. Taking students on a tour of Hardwick Hall through the eyes of Bess of Hardwick brought to life the glass in the windows, the interesting story of the Gideon tapestries and the rich and sumptuous Turkish carpets that were so valuable they couldn’t be put on the floor!

Our story of Audrey Hepburn highlights how we are able to make the occupation, much more concrete. By showing smaller details about flowers blooming, and ballet performances still continuing, it shows the softer side to occupation initially, but the details surrounding her uncle Otto’s arrest shows the direct link between resistance and escalating brutality. We feel that it is only because students have followed Adriaantje’s journey, that they gain the fingertip knowledge that helps them engage meaningfully with complex questions about occupation, collaboration, and resistance.

Making the abstract concrete is a key benefit of the storytelling approach.

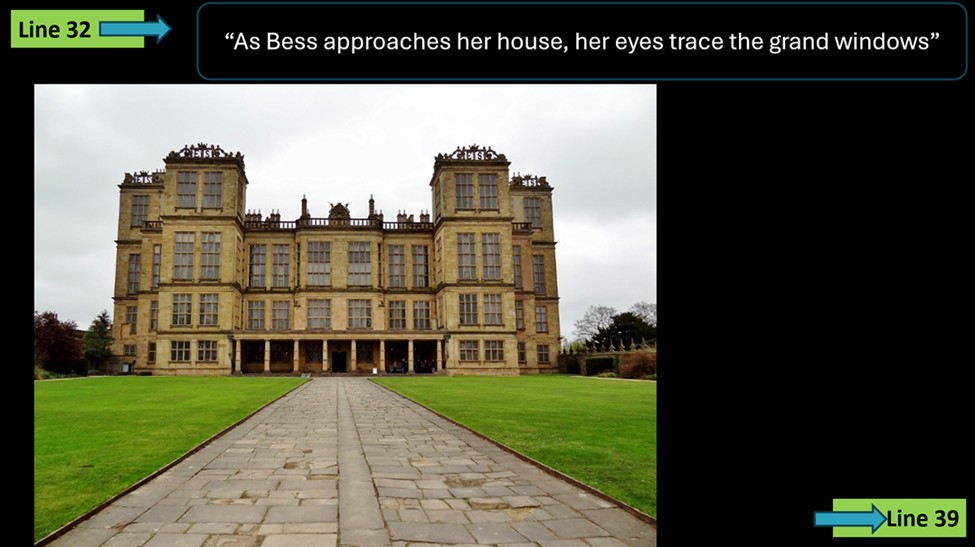

6. Using images to support world building

Using PowerPoint to share rich images on the story really helps to build worlds for the students. Having images appear on the screen during the storytelling and giving students time to pause, reflect and create an ‘imagined world’ has been hugely beneficial in making the stories land. Here’s an example from our Bess of Hardwick story.

7. Using stories to thread connections

Storytelling can make connections across time and throughout historical enquiries. Staying with the Bess of Hardwick theme, the fact that she bought the Gideon Tapestries from Christopher Hatton is a detail to drop into the story which we later revisit when teaching about Francis Drake and his naming of the Golden Hind. This approach helps students see history as a connected narrative rather than isolated facts. By encountering familiar characters and threads across different stories, students are able to build a richer schema of the Elizabethan world. This deepens understanding and reinforces learning, as well as aiding encoding as new learning is anchored in prior knowledge.

8. Make the references clear By including a bibliography of the references it helped students appreciate the disciplinary nature of history and the careful research behind historical storytelling. Without this, there’s a risk they might think history is only about the narrative. Sharing our sources gives them that essential ‘pinch of discipline’ that Rich Kennett rightly called for in his keynote lecture at the Ark Soane Conference—a reminder that good history always rests on solid evidence, not just a good story

9. Plan the takeaways

Teaching a historical story is just the start—but what do students actually take away from it? It quickly became clear that unless we make the key lessons explicit, students might remember the wrong details. That’s why it’s crucial to be clear about the curricular purpose and to build in targeted tasks that help students focus on the essential knowledge. Here’s an example from our Audrey Hepburn story.

10. The power of working collaboratively

Throughout the project, Pete and Ben took turns as the lead writer, with the other acting as an editor—helping to trim the text, verify facts, add more interesting details, and suggest ways to enrich the world-building. Each person brought valuable insights that shaped the stories in unique ways, and the project simply wouldn’t be what it is without that ongoing collaboration.

Final Reflections

Looking back, we have learned several lessons. Writing historical stories requires time and care. Collaboration improves quality and enjoyment. Integrating images, sources and reading strategies strengthens the impact. Above all, clarity of purpose ensures that stories serve as powerful vehicles for understanding rather than distractions.

Our next step is to revisit our early stories on the Making of America, improving them in light of what we now know. More broadly, we remain grateful to the wider history teaching community, whose ideas, feedback and encouragement have shaped our work. We are convinced that we are better working together than alone, and we continue to see collaboration as central to the vitality of our subject.

For us, the conclusion is clear: storytelling, when grounded in scholarship and crafted with care, is one of the most powerful tools we have to make history not only memorable but meaningful.

This is what makes the history community so utterly fabulous!