This post has been written by Meggie Hayes, History and Politics Teacher and Inclusion Lead at The Crypt School, Gloucestershire

People are queer and people have always been queer. So it stands to reason that remarkable people have been queer, leaders of the world have been queer, and ‘evil’ people have been queer. This leaves history teachers with many queer questions when teaching the past.

1. What words do we use?

2. How did queer individuals identify? Are we just speculating?

3. If sexuality/gender identity has nothing to do with their note in a history book should we even mention it? Is it appropriate?

As someone who has studied queer history for many years and is a queer teacher myself I feel comfortable giving my view on the important queer question, although I do not have all the answers.

To answer question one, we need to acknowledge question two. If a historical figure has discussed their identity and “put a label on it” then we should certainly use the identity they used. The only problem with this is very few historical figures announced to the world (or to historians) their identity and even fewer did this using modern labels. We have to be extremely careful and aware that LGBTQ language is new and evolving, and therefore putting modern labels on individuals of the past just does not work.

So what words do we use? For sexuality, if no identity is mentioned or clearly defined then the word “queer” is usually a safe “catch-all” word to describe an individual that wouldn’t identify as heterosexual. With individuals that have caused speculation such as William Rufus or any figure in the ancient world this becomes very useful. However, even with this word comes problems – queer became a slur to describe homosexuality around the 19th century – therefore context of the period studied is vital.

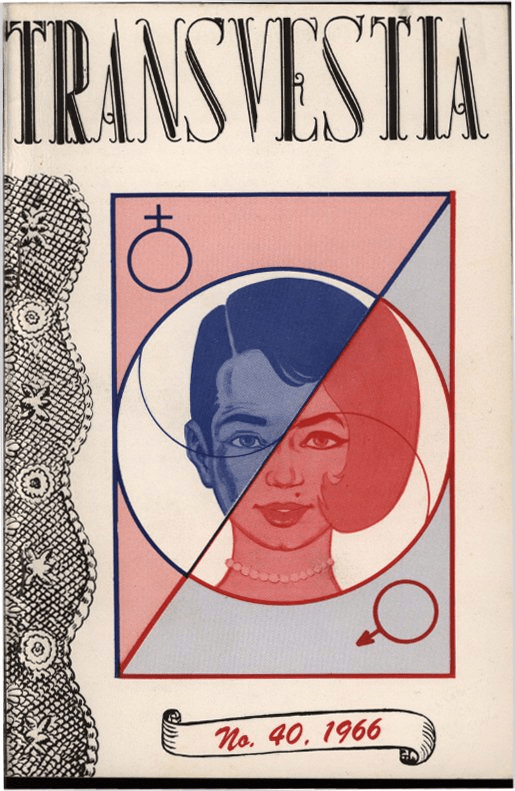

For gender, things are more complicated – the term transgender was first used in the 1960s but has only been widely used since the ‘90s therefore we face the issue of lots of different words throughout history that transgender people used to identify. Examples of these include transvestite or transsexual (both words that are highly contentious today in the trans community, and best avoided).

Therefore unless a historical culture has a clearly defined word for transgender individuals such as the native American two-spirit I would use the term transgender (rather than transsexual) where appropriate.

Where this question gets even more complicated is within the ambiguities of identity. The Mollies of the 19th century have a clear sense of effeminacy and maiden-like roles they play in their lives. However their identity has resonated with both transwomen and gay men. Therefore with more ambiguous historical moments a simple acknowledgement of this ambiguity is important. Ultimately whether some Mollies would identify as a transwomen today or an effeminate gay man would be entirely speculation. In the classroom I would teach the gay-subculture of Molly houses and Mollies and use the word queer when asked about their gender or sexual identity.

As you can see, the use of language is complicated and not a simple answer.

However, I believe my third and final queer question: If sexuality/gender identity has nothing to do with their note in a history book should we even mention it? Is it even appropriate? Is an easier question to handle.

Yes – you should mention it. Visibility is important and whilst being a member of the LGBTQ+ community often was a footnote to the many great achievements of people it was a huge part of their life! People such as Alan Turing, Bayard Rustin, Lorraine Hansberry or Emily Dickinson deserve a moment to discuss their private lives as well as their achievements and if anything it makes these people even more significant as they were successful despite facing adversity for their sexuality (especially if they were persecuted for being LGBTQ+)