Thanks to Philip Arkinstall, Curriculum Leader for History at Hardenhuish School, HA Secondary Committee member and Trustee for this blogpost. Phil guides us through the process of curriculum mapping in a history department.

Curriculum mapping our department was one of the best things we have done as a department and we began the process in 2018. It started in a department meeting, where I used pupil voice to approach the subject of curriculum review. Twice in the year we conduct surveys to find out how pupils have responded to our schemes of work. Following feedback, which is always very positive, it highlighted that some of our units were looking old and tired and that pupils wanted more. This opened up an opportunity to consider what we teach, where and how. Although we’d had our hands full with A Level and GCSE rewrites recently, it was now an appropriate time to turn our hand to Key Stage 3. During the process of us revisiting our curriculum we had mapped our history journey too. The following account takes you through the process of how we mapped out our curriculum, whilst adapting what we taught.

Having convinced the department that relooking at our curriculum was a necessary step we began with a blank piece of paper and I asked the team what history meant to them? This would allow us all to see what we had in common when we taught and what was different, which we may want to consider. The next question was what we wanted our pupils to be able to do at the end of three years at Key Stage 3? What knowledge was important, what skills were important, what sensitivities we wanted to also approach; empathy, tolerance, resilience and other human qualities. This was the start of considering the intent behind our work. It helped to frame what history meant to us and what we wanted our pupils to know at the end of their journey. This was a great way to involve the team openly from the start to get their eyes on what they thought our department should look like. Some wonderful topics of conversation came up about the types of historical topics we wanted pupils to learn and for what reason. It also elicited some wonderful ideas about how we address modern history teaching and what we all think teaching should look like. Of all the meetings I’ve conducted this by far one of the best. It gave real ownership to the department and allowed us to build something for both pupil and teacher.

The types of questions I used to prompt us were:

“Define history yourself”

“What should our pupils know?”

“What should pupils leave history at 14 being able to do?”

“Why should they know about these events?”

“What local history can complement the bigger stories we want to tell?”

“What should KS3 do to help our pupils after Year 9? – This was a rationale question

“How do we ensure pupils are ready for GCSE and A Level?”

“What type of assessments are important” – This would come at a later stage once we’d framed our thoughts

We then considered how we would teach the topics we had chosen? This meant chronologically or thematically. At this stage I’d done some research on other schools and found models of their curriculum online and some early examples of curriculum mapping to compare. These were mostly timelines of topics pupils would be taught from Year 7 to 11. We decided at the time to continue to teach chronologically, but pick out the themes as we taught each unit. This would later coincide with the school’s agenda to have a curriculum map to chart different threshold concepts across all subjects. To help with this meeting I cut cards out of all the historical subjects we wanted to teach to play around with when and where we wanted to see these topics [see appendix 1]. It was great to work in groups and then feedback on what we had considered. This also gave us a view of where would we see the same themes presented, such as monarchy, democracy, protest and conflict. At the end of the meeting, I typed up onto a word document where the same historical themes cropped up [See appendix 2]. Firstly, with KS3 and then KS4 and then 5. The document was a list but it now contained the themes across years that we taught and helped us to see what we could be emphasising when we teach our course. For example, within the First World War we had been teaching empire of course, but not really democracy or protest, which linked to the Suffragettes and protest topic we’d taught before and the civil rights work we did later on.

In our third meeting we looked at our enquiry questions and how they tied to our assessment objectives and where similar skills appear across the three years. This meeting was helped by pre-preparing the word document started at the end of last meeting [See appendix 3]. It allowed us to look at changing our assessments or enquiries to fit our intent statement about making history relevant, engaging and diverse. For those not rewriting their curriculum this is a useful way to look again at what is being taught, how it is being assessed and whether any small changes can be made to make your curriculum robust for your intended purposes. In essence this was an opportunity to see the full picture of our department’s aim. As a result, we now had a working map of historical knowledge we wanted to get across, the skills that were being assessed and a rough sequence of when would we teach it. Adding to the ever-expanding word document, I created sections for each year group and included experiences in lessons, any trips, prior learning, linked learning and oracy opportunities, such as any core books [see appendix 4]. Now we needed to consider the questions that would underpin the enquiry and steer the teaching. Often it wasn’t always an easy task and sometimes assessment titles or activities would change after we’d written our new schemes of learning. This is all part and parcel of adapting our practice and learning what works and doesn’t Having decided upon schemes and assessment objectives and the second order concept this would correlate to, we divvied up the topics and in some cases all focused on one topic as we all wanted to build it or I thought it was important as a department to look at how to model lesson planning and sequencing.

The next step was to illustrate our curriculum to pupils and parents. There were countless examples online of fancy departmental roadmaps, which show pupils where their ‘journey’ would begin and end. We didn’t like the linear nature of this approach and it led to many discussions about how and what we should show to pupils and parents. We were lucky in our school that there was no standardised format set out to fill in and that we had license to construct something that had meaning and would articulate our curriculum. After months we narrowed it down to a diagram that would illustrate themes and not chronological topics or the second order concepts. These we thought we addressed in our word document, which would be online to see what is taught and when and also our assessment grids reflect the skills they would be assessed with. We knew we wanted themes so looked at the common themes like monarchy, empire, protest etc. and considered how we could narrow them down and how to show them. We chose a tree with the branches being the themes and the historical content the leaves [see appendix 5]. Each leaf would be coloured to represent the year group they learn that topic. This was organic for us and allowed us to remove and add trees whenever the curriculum changed. It was easy to look at and use in lessons to show pupils what they were looking at. Why a tree you may ask? Well, we considered it to be ancient, like the study of history, ever evolving like a tree does, reaching for more light and understanding and fundamentally we thought a tree was always present during historical change. From historical events like the industrial revolution, where trees were uprooted, to revolutions that began under trees, monarchies begun from them and how it has been used to construct weapons, ships, buildings. Really it was something that we thought would stand out too. Whatever choice you decide it is important that at the ‘root’ of the map are your values and intent for the subject.

During the course of this first year we also knew that very few departments rewrite everything so we planned to do this rewrite over the course of three years. Covid was a winner for 2020 in terms of planning time, as we could get quite a few lessons made and resourced in that year. Time is definitely the thing to bear in mind if you embark upon this yourselves, but I would say that the pupils have really benefitted from the new schemes of work which have a much wider sense of diversity Medieval Queens, Empire, the Industrial revolution in our locality and a much wider distribution of world histories. We have kept some old favourites like the Normans, but instead look at the significance of the Normans instead of why they won the Battle of Hastings. By mapping out the curriculum alongside this rewrite, we have a much better consolidated approach to teaching our lessons and also in ensuring the pupils experience consistency. Our next step is to create a top slide for any presentations we use to showcase the links across the curriculum and to create top sheets for non-specialists to illustrate the core concepts and language every pupil needs.

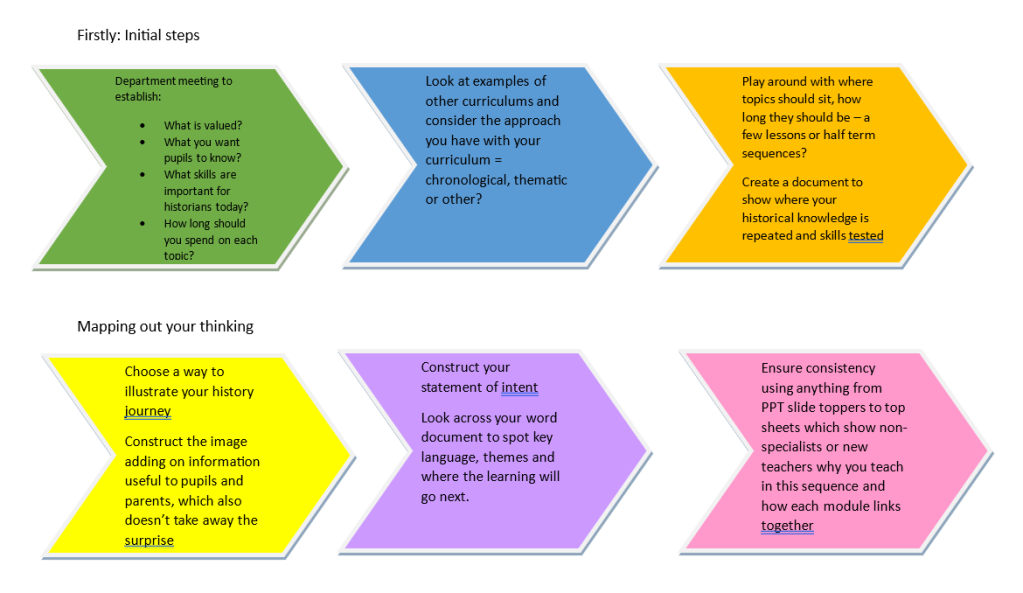

By breaking the process of initial thinking down first it then became an exercise of managing the workload and supporting each other in the creation of new materials. The diagram below gives an indication of how we approached it.