Thanks to Mike Hill, Head of History, Ark Soane Academy, and a member of HA Secondary Committee, for this blogpost to help with the planning of enquiries.

Over the last term, I planned seven new enquiries and I am currently working on an eighth. I feel out of breath typing this. Planning these enquiries has sometimes felt like trial by ordeal, but it’s also been a great exercise in hard-nosed pragmatism. Here are five rules of thumb that I’ve found useful when it comes to the nuts and bolts of enquiry planning.

- Don’t pack too much in.

Short and punchy enquiries are often the best. I struggled with this when I first became a teacher. The past presented so much ground to cover. How could I possibly get pupils to understand the Norman conquest without also teaching them in depth about Anglo-Saxon society? Could my pupils really understand what changed after 1066 without also understanding why these things changed, and for whom, and where, and when, and how fast…?

This often resulted in sprawling enquiries that went on for weeks (or entire half-terms). Pupils inevitably lost track of the big picture as well as the finer detail. The enquiry question couldn’t keep all the moving parts together and lost its power to make the little examples ‘sticky.’

I’ve found that my better enquiries now tend to be shorter but punchier. They span about four or five lessons, with one conceptual focus. For example, I can’t cover the nature of change, speed of change, and extent of change all in one enquiry. It’s better to focus on one of these aspects and consider where the others might feature across the curriculum – and where they can then take centre stage.

It’s good to remember here that enquiries and ‘topics’ are not the same thing. Instead of teaching a sprawling nine-lesson enquiry on seventeenth-century Britain, for example, it’s much better to split this ‘topic’ into two shorter enquiries with separate (though perhaps linked) focusses; for example, the Civil War and the Restoration.

- Keep the enquiry question straightforward.

Good enquiry questions bring together pith, puzzle, and rigour. Writing them can be extremely fun and difficult – but it’s easy to get carried away with them too. In my experience, enquiry questions that sound good to other history teachers (because they use a clever metaphor, word play, or poetic turn-of-phrase) can often fall flat with pupils in the classroom.

I now try to resist the temptation of the overly clever enquiry question. Keep it short, keep the language simple, keep it accessible. For example, “How did the East India Company rise to power?” might sound plain, but it’s accessible and to the point. I now prefer these questions to word plays or quotes such as “Did the East India Company really ‘begin in commerce and end in Empire?’” The latter might look good on a curriculum document, but it won’t land as well in the classroom.

Bear in mind that your enquiry questions are for your pupils – not for other adults to admire! As a rule of thumb, try to read enquiry questions like a pupil who finds history hard. Will the question make sense to them? Can they have a good go at wrestling with it (and ultimately answering it) without tightly scaffolded writing frames or other crutches?

Enquiry questions are like jokes: they’re not good if we have to explain them. When I find myself repeatedly paraphrasing an enquiry question in the classroom, I tend to bin it and use the simpler, paraphrased version instead. In case of doubt, keep enquiry question simple.

- Simplify – or make complexity the thing.

The past can feel like an unwieldy beast, infinitely interesting and infinitely complex. It’s notoriously difficult to wrestle this complexity into teachable shape; into something that makes sense to children in relatively simple terms without being simplistic. Getting complexity right in history is really, really hard. It involves lots of trial and error.

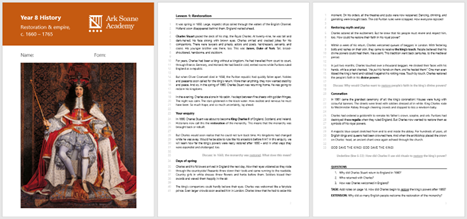

I recently planned an enquiry on the Restoration period for our Year 8s, which digs into the nature of the monarchy after 1660. Was the monarchy really brought back as it had been before, or was it forever changed? The last ‘beat’ of the enquiry is the Glorious Revolution in 1688, and the slow shift in power between monarch and parliament.

As I wrote the final lesson on 1688, I felt my history teacher conscience tugging at me. Don’t you have to problematise the phrase ‘Glorious Revolution’ here? Surely, you’re not going to leave that uncontested? Perhaps add a little paragraph here on the Jacobites in Scotland, and the Williamite War in Ireland, and the Stuart pretenders, and the Nine Years’ War, and the long lines of continuity and conflict that stretch right up to the present day…

But in the end, I cut my losses and chose to leave the complexity around the term ‘Glorious Revolution’ out. There was just no way I could do justice to this here without pulling pupils away from the main focus of the enquiry, and thus really confuse them.

The problem with complexity in history is that it usually takes the form of abstraction; and the only way to untangle the abstract is to slowly guide pupils towards it, through lots of concrete stories and examples. Stories of Jacobite loyalists secretly toasting the king over the water. Stories of the Battle of the Boyne and its long shadows. Stories of historians arguing over the right terms and phrases. All this takes space, and time.

However, if I decided that I really do need to dig into this complexity, then I’d have to make it the focus of another enquiry. For example, I could plan a separate enquiry around the question “Was 1688 really a ‘glorious revolution’ for everyone?” There’s a case for doing exactly that – but if I don’t have enough space in the curriculum, then it’s better to leave this particular can of worms unopened (rather than cramming it into an already complex enquiry).

History teachers can’t do complexity on the fly. In case of doubt, either simplify or make the complexity the main thing. Every can of worms needs space and time to breathe and wriggle.

- Write it all up in extended prose.

I’ve found that flawed resourcing can easily ruin good planning. When I was a trainee teacher, I often felt disappointed when the complexity that I’d planned into an enquiry didn’t materialise in the classroom. I now think this was due to the types of resources or ways of teaching that I used then: worksheets, card sorts, slides, source printouts, and other classics. The problem with these resources is that they communicate information in ways that are often patchy or transient.

By patchy, I mean that it’s hard (or simply impossible) to fit enough information onto worksheets and cards. Much of the texture that is vital for rich understandings then remains unsaid or implicit: the speed of events in an unfolding narrative, for example, or the rich contexts of a historian’s interpretation.

By transient, I mean that these resources often communicate information once and only once: for example, pupils might encounter important (and complex) events on a slide – and when the slide deck inevitably moves on, all this information disappears into an inaccessible nether zone. Pupils cannot re-encounter or check it again, which often impedes deeper (and richly textured) understandings

In my experience, a better way to resource enquiries is to codify what we want pupils to learn into extended text. Write it all up, then read it together in the classroom – with lots of joy and intrigue and suspense. This way, everything we want pupils to learn is right there in front of them, allowing us to hit all the notes we want to hit and our pupils to re-encounter tricky things at various points in the lesson.

In my department, we usually read a double side of A4 with pupils in a lesson (c. 700-800 words) – with line-numbers, headings that chunk texts into ‘big ideas’, and tasks or questions all in one place. This makes it so much easier for us to teach exactly what we want pupils to understand – and to make sure that all pupils, across classes, learn the same curriculum and get the same deal.

- Complete your own tasks.

I know this seems blindingly obvious, but it’s easy to miss out in practice. Once you have written your texts, questions, and tasks, always complete your own answers to these tasks as well as your enquiry question.

Importantly, do this using only what you’ve written explicitly into your resources. Be strict with yourself here. It’s great if a pupil brings additional knowledge to the table (which they’ve picked up outside school), but our tasks should be doable with what we’ve directly taught in class. Otherwise, puzzle can quickly collapse into confusion, and desirable difficulty into frustration.

It can be useful to ask here:

- Do my resources codify enough little examples for pupils to draw on when they answer my questions?

- Is the link between these little examples and the enquiry question straightforward, or is it convoluted?

- How will pupils who find history hard get on with this? Can they have a good go, feeling challenged and successful? Have I given them the tools to do the job?

It’s easy to misjudge how accessible these things really are to others. I’ve found it useful to give resourced enquiries to a colleague, asking them to have a go at the tasks and enquiry question. Was there anything that confused them? Did they pick up on everything I wanted to get across?

Planning good enquiries is really tricky, and there’s so much more to it than these five rules of thumb. However, getting the practical nuts and bolts right is just as important as the deeper curricular thinking that sits behind a great enquiry. In an enquiry that really lands in the classroom, theory and mechanics usually dance with each other in ways that launch pupils into puzzle, narrative, argument, and wonder. Perhaps these five rules of thumb can help with one side of that dance.

For more on the practical theorising of the enquiry question you could go to: