Thanks to Alex Fairlamb for this blogpost. Alex Fairlamb is a Senior Leader in charge of Teaching and Learning and CPD, based in the North East. She is an SLE and an ELE. Alex is also a member of the Historical Association Secondary Committee. Alex tweets as @lamb_heart_tea

Take two minutes to read the statement below and then reflect on the questions:

“The curriculum in my department is diverse and represents the communities that we serve. It ensures the children have a global understanding of the world, and they explore and study differing perspectives and experiences in meaningful ways.”

- How far can you agree with this statement?

- If you can agree, how do you KNOW you can? What do you do within and beyond your school?

Now consider these questions:

- When considering people who are disabled, how present are they within your curriculum?

- Where?

Disability and the Tudors

During a talk by Phillipa Vincent-Connolly in 2022 on Disability and the Tudors, she asked us to review a portrait. We were asked to examine what we could see and who we could see, and what background knowledge we had to explain the source. Answers mainly centred on the royals pictured and what we knew of them, some others focused on the dressings of the court – the tapestries etc – and what this told us about life in the Tudor court. Eventually, a few noticed the two people in the background on the left and right side. But no one could say who they were and why they were there, just that it was curious that a monkey was pictured on the shoulder of the male.

So, who were these people? Why were they in the portrait? And why didn’t we know anything about them?

Sitting there, I had to admit that I had little that I could contribute to explain the two people in the image. It was at this point that I realised that my knowledge of disability history was extremely limited. I could put my finger on knowing that I taught about disability during Year 9 WW1 and the GCSE History of Medicine WW1 paper, used paintings by Otto Dix depicting disabled veterans when explaining Weimar art and taught the persecution of disabled people by the Nazi regime as part of the GCSE Weimar and Nazi paper. But I could not say that I explicitly taught it elsewhere. Increasingly, I began to worry that if this was the only disability history that I was teaching, was I in fact falling foul of what Plumb warns us of in the first part of this quote, that ‘Disabled people from the past can often be presented in reductive or stereotypical ways; in some cases we found taking a fresh look at historical records revealed those same lives filled with opportunity and autonomy, influence and adventure, love and joy.’

When Phillipa explained the portrait and the history behind it, I became acutely aware of how much I had unintentionally omitted disability history from many enquiry questions in spite of the content being readily there for me to weave in. What did she reveal about this portrait?

Figure 1: My collated notes on the portrait taken from Phillipa’s talk and book

Phillipa revealed that right before our eyes, disability history was in plain sight. Moreover, for me with limited knowledge of disability history during this period, she smashed myths and misconceptions about what I thought attitudes towards disability during the Tudor period would be.

“Before the rise of ‘natural fools’ like William Somer and Jayne Foole, fools were clothed to represent their position and to meet practical demands. Now, natural fools were adopted in a new kind of role, lavishly dressed to set them apart from the other servants, as so-called ‘pets of the court’ (Phillipa Vincent-Connolly, 2022)

Within the talk and the book, through characters such as Jayne Foole, what Phillipa made clear is that some disabled people had unique opportunities in Tudor England and this can tell us about Tudor attitudes towards disability. For example:

- Education: Jayne Foole could speak several languages and could write, which tells us about education as the result of her benefactors.

- Travel: Jayne Foole had been to Jerusalem.

- Companionship: Loyalty to Anne Boleyn during the Coronation

- Behaviour – freedom – as above

- Position. Seen as source of wisdom and humour (compared to treachery and plotting at court) Remarks treated with reverence

- Access to comfortable living conditions: inventories of clothes commissioned – green satin cap, records in Privy Purse records, keeper

Back in school, I began to consider where and how disability history could be woven into our Tudor history enquiries in KS3-5. Before I pushed forward with committing content to an enquiry, I wanted to first of all make sure that I was approaching disability history in an appropriate way – that my keenness didn’t supersede thoughtfully considering how to weave disability history in and avoid the traps of ‘inspiration porn’ or accidentally reinforcing derogatory stereotypes or using terms which are inaccurate. As a non-disabled person and someone new to researching disabled history, it is something that that could very realistically happen, despite whatever the best intentions might have been. Therefore, it’s important to plan for the below:

How you will ensure that the pupils will have a clear definition of what you all currently understand to be disability

- Explanation that this definition has changed throughout history; and that stereotypes and derogatory language is common BUT that it is not permitted to use that language now.

- Clear framework of how to talk about disabled history

- Clear explanation of why – anti-ableism

Avoid stereotypes of disabled people – laughed at, pitied.

Balance with stories of

- role within the community

- role at court

- significant individuals (Nelson, Tubman)

- activism

- individual stories to bring their narrative to the front and centre

- typicality of likelihood of injury causing a disability due to disease (Great Plague), work (machinery in the IR) and conflict

- their voice e.g. Jayne Foole

Source selection

Like the Holocaust, images selected which do not dehumanise (taken without consent) and are not used for shock

Below are some notes to give an overview of some aspects which could be woven into enquiry questions relating to Tudor England:

- Natural Fools. Thomas More and Henry Patenson (man who was disabled) – lived with him like a son. Patenson is depicted in the Notley Priory painting of the More family and was treated as ‘Master Harry’, as though he were a member of the More family. It is thought that Patenson had a learning disability and was what the Tudors would have considered a ‘natural fool’.

- Depictions of disabled people. Henry VII used advances in printing to caricature Richard III’s disability (scoliosis) as part of propaganda. Yet Richard III was able to fight in armour.

- Henry VIII. Injury led to mobility aid use

- Closure of the monasteries. Impact upon hospitals and the sick and disabled. Greater reliance of women in the home for care. Petiton in 1538: ‘the miserable people lyeing in the streete, offending every clene person passing by the way’. Gradually, caring for disabled people became a civic duty, not just a religious matter. Rich benefactors still funded buildings but it was to enhance their reputation, not to save their souls. In London, new hospitals were built and some old ones were re-founded.

- Medicine. Treated with religious, psychological, astrological and traditional remedies.

- Poor Law 1601. ‘Impotent poor’ – natural disabled, dim of wit, blind etc. marks the first official recognition of the need for state intervention in the lives of disabled people. Household or domestic relief or funds to support

- Tudor society. Disabled people were married – survey in Norwich: 1570 blind baker William Mordewe worked due to support from his wife Helen. survey of the poor in 1570, established that almost all the disabled men and most of the disabled women were married to non-disabled people and many had children. They were part of the community

- Disabled soldiers and sailors. Senior Officers called for hospitals – hospital for the maimed (Berkshire, 1599). Chatham Chest set up in 1590 to pay pensions for those who had ‘lost their limbs or disabled their bodies’.

Disability history throughout a progression model

Having explored the Tudor period, I began to consider how else disabled narratives could be woven through a progression model as one of the threads that begins in Year 7 all the way to Year 13. As I did so, it became even more apparent how little disability history I had previously included in enquiries that I taught. Below is an overview of where I identified disability history could be included in the topics we study.

Figure 2: Where disability history could be woven into a progression model and how topics could be developed

Further strategies to weave in disability history

As well as substantive knowledge, there are further ways that you can develop disability history within your curriculums.

- Scholarship. Texts such as:

- Disability and the Tudors, Phillipa Vincent Connolly

- Unwell Women, Elinor Cleghorn

- The Facemaker, Lindsay Fitzharris

- Sources

- The portrait earlier in the blog

- Portrait of William Somer

- Photograph of Rosa May Billinghurst surrounded by policemen and her testimony of her treatment during Black Friday

- The Disabled Soldier’s Handbook 1918

- Photograph of a person being trained to weld as part of the Disabled Section of the Munitions Training Scheme during World War Two

- Hinterland and homework

- Meanwhile, She – Harriet Tubman

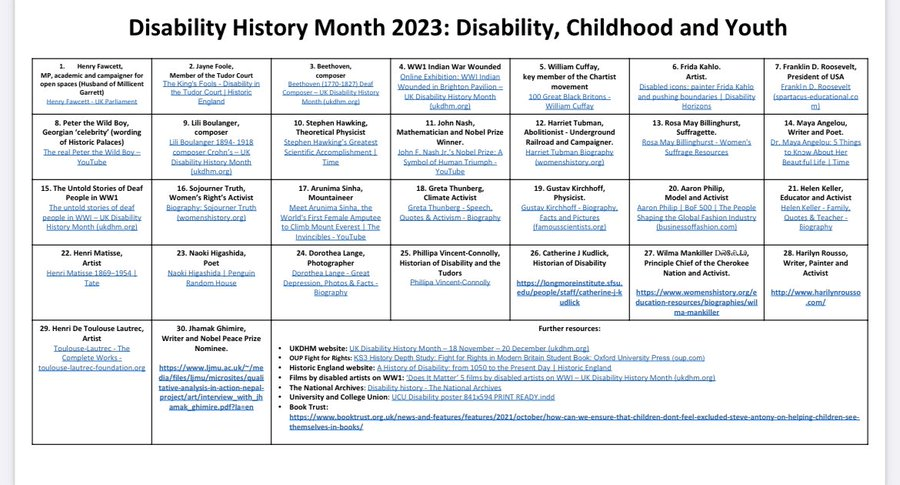

- Disability History Month Calendar (figure 4)

Final thoughts

Disability history is an important thread to have woven into our curriculums. Through careful consideration within departments, it can be effectively and meaningfully woven in so that enquiries can be broadened and so that previously unknown narratives can be shared with our pupils. As mentioned earlier, one of the key things to secure before embarking upon threading through disability history is how you frame and discuss disability as a team and with the pupils. Moreover, how do you ensure that the narratives that you include are meaningful and align with appropriate representations of disabled history including language and imagery (avoiding the mistakes of inspiration porn etc.)

Figure 3: Disability History Month calendar

Useful further reading:

- Home From the War: What Happened to Disabled First World War Veterans – The Historic England Blog (heritagecalling.com)

- Nothing About Us Without Us – People’s History Museum: The national museum of democracy (phm.org.uk)

- Holocaust Memorial Day Trust | Disabled people (hmd.org.uk)

- UK Disability History Month – 18 November – 20 December (ukdhm.org)

- UK Disability History Month 2021 Online Launch Tickets, Thu 18 Nov 2021 at 19:00 | Eventbrite

- A History of Disability: from 1050 to the Present Day | Historic England

- ‘Does It Matter’ 5 films by disabled artists on WWI – UK Disability History Month (ukdhm.org)

- Disability history – The National Archives

- HA recorded webinar: Exploring representations and attitudes to disability across history

- TH 173 article: Hidden in plain sight: the history of people with disabilities

2 thoughts on “Disability and the Tudors”